At Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklynites remembered loved ones lost on 9/11 where they rest, rather than where they lost their lives.

More than 100 victims of 9/11 are interred at the cemetery — 78 who lost their lives that day, and dozens more who died from Ground Zero-related illnesses in the years after. As the sun set on Sept. 11, 2024, Brooklynites gathered among the gravestones overlooking the Manhattan skyline. There were no suited-up military or police personnel or politicians, no big speeches.

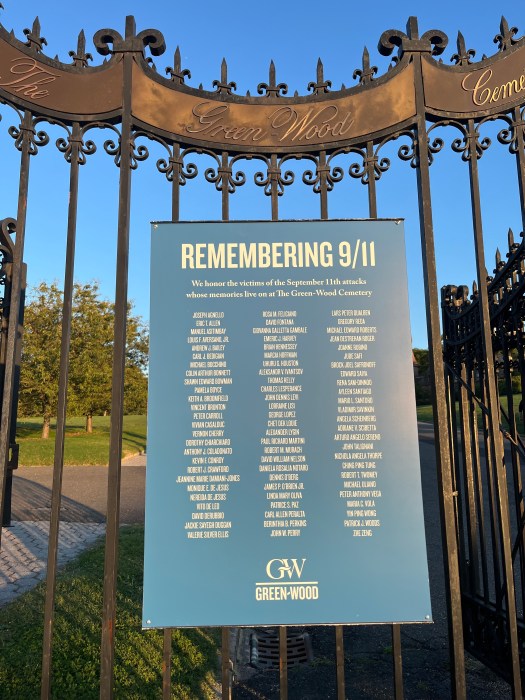

Musician George Stass sang quiet renditions of “Fire and Rain,” and “Wildflowers,” and “Every Grain of Sand.” When the sky was dark and the Tribute in Light visible against the sky, two Green-Wood staffers stood to read a list of more than 70 names — most of whom are buried at there, some who are not.

Gabrielle Gatto, coordinator of public programs at Green-Wood, and Theresa Wozunk, a death counselor, worked together to plan the event, a departure from their usual memorials.

The idea for a quiet evening memorial came to them last year, Wozunk said, and they worked with the 9/11 Museum and Memorial to organize Wednesday’s event, centered around the Tribute in Light.

“I’ve always thought it would be such a beautiful viewing point, and a really safe space for New Yorkers who don’t feel comfortable going to the museum but want to pay their respects in a way,” Wozunk said. “And what a great, beautiful place to sit and reflect.”

More than two decades after the attacks, some New Yorkers struggle with big memorials, like the reading of the names of victims at the 9/11 Memorial on the footsteps of the Twin Towers. Gothamist reported that in the last year, only 6% of visitors to the 9/11 Museum were from New York City. Green-Wood wanted to offer those people a peaceful place to grieve together.

The cemetery now serves as a sort of community space, Gatto said, especially since the pandemic, when many Brooklynites found peace and solace walking the grounds. The 9/11 ceremony was an extension of that ethos, a chance for people to grieve different people in different ways. Gatto included her uncle, a former FDNY captain who died in 2016 from 9/11-related cancer, in the list of names.

“My uncle is not interred here, but we continue to memorialize him in many different ways,” she said. “This can be a place of memorialization for anyone, anyone that needs to grieve and maybe do it in an accessible place that doesn’t have to be so charged, or they just have an area to kind of peel off to.”

Dozens of Brooklynites settled in on Green-Wood’s hills for the ceremony, some in large groups, others separated in pairs or alone on the grass. A few asked Gatto and Wozunk to include their loved ones’ names in the reading.

Matt Pinner sat on a set of low stairs with his two-year-old daughter. He moved to New York City from Colorado in 2020, and said that while his experience of 9/11 was different from those who lived in the city at the time, he knew he and his family wanted to acknowledge the day in some way — which brought them to Green-Wood.

“It’s a unifying event, I like ritual and ceremonies and traditions,” he said. “Anything that brings people together, gives you an excuse to go out in the world and be among people. We all grieve together. No one should do that alone.”

Andrew Schneider attended the ceremony on his own, to support a friend who was playing music there. He moved to New York City in 2003, when the city was still reeling in the aftermath of the attacks. On Sept. 11, 2003, he said, the anniversary had a palpable presence, one that has dissipated somewhat with time.

He didn’t lose anyone on 9/11, and felt at first like he shouldn’t be there at the memorial. But he wanted to hold space for the people that did, and remember their loved ones with them.

The memorial felt different, too, because he recently lost his father Elroy. Grieving is a long and complex process, he said, one he just started — but finding a space to grieve collectively felt good.

“I was over here before, I was thinking memorials are so nice because they’re in honor of the people who are no longer with us, but they’re for the people who are still here,” he said.

Included on the list of names read at Green-Wood on Wednesday were Joseph Agnello, Peter Vega, and Vernon Cherry, three Brooklyn Heights firefighters who were found together and buried side-by-side; and Monique De Jesus, a 29-year-old administrative assistant at Cantor Fitzgerald.

Schneider said he watched a lot of old videos of his father after he died all on VHS, with the fuzzy quality associated with the medium. The news footage from 9/11 has the same quality, he said.

“When I hear the names, I picture those people in that media form, like frozen in time, like they didn’t age with us,” he said. “Things got more HD, more crystally-clear. And those memories, they’re not fading, but they take on a different sort of quality because of the medium that they were on.”

Wozunk also wanted to pay tribute to Green-Wood itself, and the people who worked there during and after 9/11.

“The cemetery itself was integral in 9/11, and what this place has absorbed for various tragedies over the years is monumental,” she said. “The role that our gravediggers played, the role that our president played on that day and the months after, I just think is something to be celebrated and heralded.”

Cemetery workers were faced with the tragedy head on, she said, as they were tasked with laying victims to rest. They grappled with similar circumstances during the pandemic, when thousands were dying from the virus.

Isaac Feliciano, a now-retired Green-Wood foreman, lost his wife Rosa on 9/11. The smoke and fire were visible from the cemetery.

“He was here at work and had to see everything and still carry on and make sure he could be there for other families and for his own,” Gatto said. “We call [cemetery workers] last responders … it’s holding space for families, in those very last and final moments.”

Rosa is buried at Green-Wood, and her name was read on Wednesday night. In 2011, Feliciano told the Daily News that he would not visit Ground Zero to remember his wife — he much preferred to honor her at Green-Wood, under the memorial tree he planted for her.