Turkey-allied Azerbaijan is seeking dominance over Armenian-controlled Nagorno-Karabakh and two key land corridors. Russia and Iran may stand in the way.

A man near Yerevan on September 26, 2021, mourns a relative killed in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war that ended with Armenia’s defeat against Azerbaijan. © Getty Images

A man near Yerevan on September 26, 2021, mourns a relative killed in the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war that ended with Armenia’s defeat against Azerbaijan. © Getty Images

- The conflicts highlight Russia’s weakened influence in the region

- The Lachin and Zangezur corridors are vital routes for Azerbaijan

- Armenia is counting on Russia and Iran to thwart Baku’s aims

On January 23, United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken made a seemingly innocuous request to Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev: Lift the blockade from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh, the ethnically Armenian exclave inside Azerbaijan.

There were humanitarian reasons for this plea. For the 120,000 ethnic Armenians trapped inside the region, the Azeri blockade has resulted in shortages of food, gas and electricity, plus disruptions of internet services. The causes, which began on December 12, seem rather minor – environmental activists demanding the right to monitor alleged illegal mining operations in Nagorno-Karabakh.

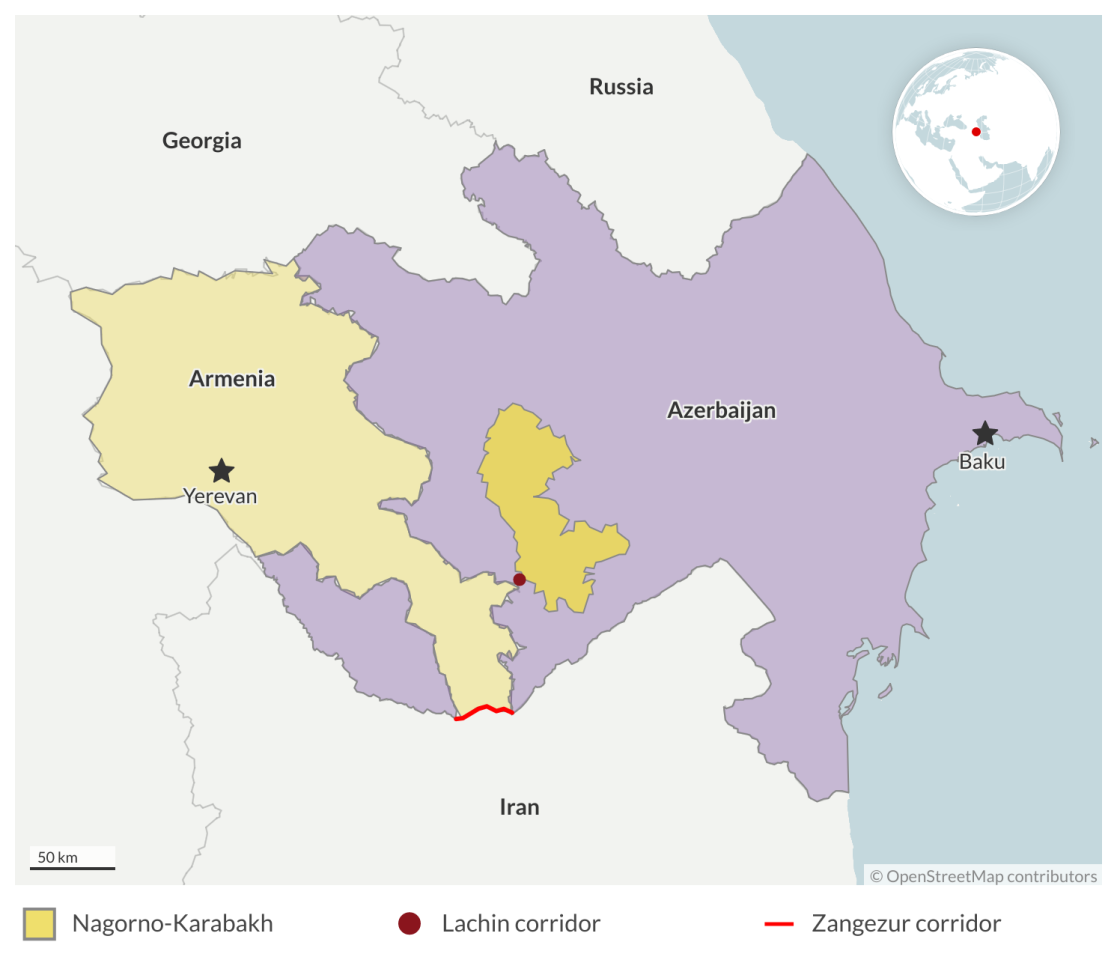

Known as the Lachin corridor, the road connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh is nominally under the control of Russian peacekeeping forces. As agreed in an armistice deal brokered by Russia in November 2020, it should be open for commercial traffic. According to Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, it is not open. In a separate conversation with Secretary Blinken, he voiced concern about the humanitarian consequences.

Casual observation may suggest this is a tempest in a teapot. Not so. It is a warning sign of an underlying conflict that already reaches far outside the region.

The driving force is the weakened position of Russia, a direct consequence of its brutal war against Ukraine. As the Kremlin no longer has either the clout or credibility to enforce its version of order in the South Caucasus, or indeed in Central Asia, regional actors are raising the stakes in their own games for influence.

The most immediate consequence is to scupper any hopes of a peace settlement between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Political developments will be marked by the threat of a resumed military offensive by Azerbaijan, which would be supported by Turkey and deeply resented by Iran. The outcome will be a geopolitical transformation of the South Caucasus, which will shape transport infrastructure through the region.

War between Armenia and Azerbaijan has been going on sporadically since the early 1990s. When the first phase concluded, in May 1994, large swaths of Azeri territory were occupied by Armenian forces. Nagorno-Karabakh was de facto incorporated into Armenia. The local leadership in Stepanakert proclaimed a Republic of Artsakh that was not recognized even by Armenia. It was the first in a series of “frozen conflicts” in post-Soviet space.

From 1994 onwards, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe maintained a mission to broker a solution, but its struggles served mainly to reflect the marginal influence of international organizations. What kept the conflict frozen was Russian military clout. Although nominally on the side of Armenia, Moscow sought to maximize its influence by supplying arms to both sides.

Winners and losers from the Karabakh war

The balance shifted in September 2020, when Azerbaijan launched an armed invasion to reclaim Armenian-occupied territories. The action had been in the cards for some time after Baku used its oil wealth to beef up its military. The novelty in its bid was that it had found new and more reliable allies. It secured advanced weaponry from Israel and received much support from Turkey, including the Bayraktar drones that would become famous in the war in Ukraine. The outcome was a rout of the Armenian forces.

By making life difficult for the inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh, Baku hopes to achieve three goals.

On November 10, following six weeks of intense fighting, the Kremlin managed to secure an armistice. It had three important features, the consequences of which are now being played out. The first was that it preserved Armenian control over much of Nagorno-Karabakh, unacceptable to Azerbaijan. The second was that it stipulated the creation of two important corridors – the Lachin corridor, providing a lifeline for ethnic Armenians left inside landlocked Nagorno-Karabakh; and the Zangezur corridor, to provide a link from Azerbaijan across Armenian territory to Baku’s Nakhichevan exclave. The third was that Russia received a five-year mandate to deploy about 2,000 peacekeepers.

The current blockade drives home that Russia is too weak to police the agreement, and it suggests an obvious Azeri game plan. By making life difficult for the inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh, Baku hopes to achieve three goals. One is to force the leadership in Nagorno-Karabakh into submission. The second is to force Armenia into accepting an opening of the Zangezur corridor and the third is to compel the Russian peacekeepers to withdraw.

Baku is emboldened by the fact that Armenia has been denied support from the Russia-led Common Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), of which it is the only member in the region. The Russian response to its appeal for help was that the 2020 invasion was not an attack on Armenia but merely on the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh. The CSTO has since been cold-shouldered both by Kyrgyzstan, which canceled planned drills in its country and Armenia, which has said it sees no point in hosting drills planned for this year.

The demise of the CSTO into near irrelevance is a powerful symptom of Russian weakness. The vacuum left behind will be filled by two competing alliances, an ascendant one between Turkey and Azerbaijan and the other between Russia and Iran.

Although Azerbaijan’s struggle to reclaim control over Nagorno-Karabakh is partly a nationalist cause, it boils down to securing the Zangezur corridor. The main impact of Armenia’s seizure of large swaths of Azeri territory was to interdict a vital Soviet-era transport corridor. Drawn along the Caspian Sea, it ran from Russia to the south of Azerbaijan where it turned west to Turkey and Armenia, hugging the border with Iran. Having ended up in a war zone, it could no longer be used, and rapidly fell into disrepair.

Turkey consequently became dependent on Iran for transport to Central Asia, a situation marked by increasing conflict, ranging from raised transit fees to harassment of Turkish truck drivers. Ankara is presently keen on promoting a peace deal between Armenia and Azerbaijan that would feature a reopening of its former direct link to Central Asia.

But Armenia has found ample reason to drag its feet. It opposes the proposed extraterritoriality of the Zangezur corridor, concerned that it would run along the border with Iran. The arrangement would block vital access to a friendly neighbor and risk placing the management of critical water resources from the Aras River basin in the hands of Azerbaijan.

The bulk of Armenia’s border in the south is with Turkey and with the Nakhichevan exclave. There are only two small stretches that offer passage into Iran, one of which is between Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan. If the Zangezur corridor becomes reality, the only remaining lifeline to Iran would be a small stretch between Nakhichevan and Turkey.

Baku has grown increasingly insistent that a peace deal must be consummated, and that work must begin on getting the Zangezur corridor operational. On January 10, President Aliyev accused Armenia of reneging on its obligation, ominously noting that “whether Armenia wants it or not, it will be implemented.” Although he was careful to add that Azerbaijan has no intention to launch another war, the implied threat was clear.

The outcome if Turkey and Azerbaijan emerge as winners would be infrastructure investment that is geared toward providing energy from Central Asia and the Caspian basin into Europe.

What may still serve to thwart Turkish-Azeri ambitions is the deepening link between Russia and Iran. Deliveries of Iranian Shahed drones have already been helpful to Russia’s war against Ukraine. If cooperation is extended further, it could have consequences far outside the region. Reports have suggested that Iran may deliver ballistic missiles in return for advanced Russian fighter jets and possibly even help in completing its nuclear weapons program.

Armenia has every reason to bank on this alliance. Aside from Russia, which has played both sides, Iran has been its only friend. It has long provided energy and other critical supplies via roads across the common border, and its motivation for providing such support is reliable self-interest.

Iran is concerned about the implications for its own security from a peace treaty that allows the Zangezur corridor to be launched. There are more than 20 million ethnic Azeris living in Iran, mainly in the north, and it is no secret that any Israeli attack on Iran would be supported by Baku. Such concern has been augmented by Azeribaijan’s recent decision to open an embassy in Israel.

In the runup to the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh, the Iranian army conducted drills along the Aras River, which separates the two countries. Those drills included a simulated building of temporary bridges, implicitly threatening an armed invasion. An Iranian Azeri-language broadcaster warned that “anyone who looks at Iran the wrong way must be destroyed.”

Azerbaijan countered with drills of its own that featured participation by Turkish armed forces. The Azeri press also reported that the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) had provided vital military supplies to Armenia and sent military advisors to Armenian forces inside Nagorno-Karabakh. Although the veracity of the claims may be disputed, the conflict is heating up. After its military exercises along the Aras, Iran upped the ante even further by opening a consular office in Kapan, located in Armenia’s southern Syunik province, through which the Zangezur corridor would be drawn.

Iranian fears of closer relations between Israel and Azerbaijan were enhanced by the bombing campaign that struck several Iranian cities on the night of January 29. Presumably orchestrated by Israel, it targeted vital military and industrial sites, including the headquarters of the IRGC. Although it is unclear what the main objective was, it sent a powerful message of Iranian vulnerability.

Developments can move in two very different directions in this geopolitical transformation of the South Caucasus. One features a stalemate in the war in Ukraine, a gradual recovery of Russian strength and a deepening relationship between Moscow and Tehran. The outcome would be to counter the growing influence of Azerbaijan. Russian peacekeepers would reassert control over the Lachin corridor. Iran would begin sales of weapons to Armenia, notably the Shahed-136 drones, and the Zangezur corridor would be stalled. The longer-term investment would be aimed at promoting the north-south transport corridor that has long been favored by Russia and Iran.

The alternative scenario features a defeat for Russia in Ukraine and effective sanctions against Iranian exports of weapons. This would embolden Azerbaijan and Turkey to push through the Zangezur corridor, to further erode Russian influence in the South Caucasus and to shut Iran out of the region. It is worth remembering that during the 44-day war in 2020, Azerbaijan not only shelled targets in Nagorno-Karabakh but also targets inside Armenia proper. It remains in a position to do so again, and Russia may be too weak to prevent it.

The outcome if Turkey and Azerbaijan emerge as winners would be infrastructure investment that is geared toward providing energy from Central Asia and the Caspian basin into Europe. There would be many winners. Turkey is only too happy to become a major energy hub. The European Union has already courted Baku for gas while dialing back criticism of Azeri human rights abuses. And the U.S. would be happy to see Russia pushed out. It does look like the most likely outcome.

Receive insights from our experts every week in your inbox.

The post Geopolitical transformation in the South Caucasus first appeared on The News And Times – thenewsandtimes.com.